In Michael Flynn case, Judge Sullivan’s gross overreach turns justice into mob rule

The case against Micheal Flynn is abusive and should be dismissed, as the Justice Department requests. But Judge Emmet Sullivan has other ideas.

Jonathan Turley

Opinion columnist

Authored by Jonathan Turley, op-ed via USA Today,

The case of former national security adviser Michael Flynn is rapidly moving from the dubious to the preposterous. U.S. District Judge Emmet Sullivan is being widely applauded for resisting the dismissal of a case that the Department of Justice insists cannot be ethically maintained.

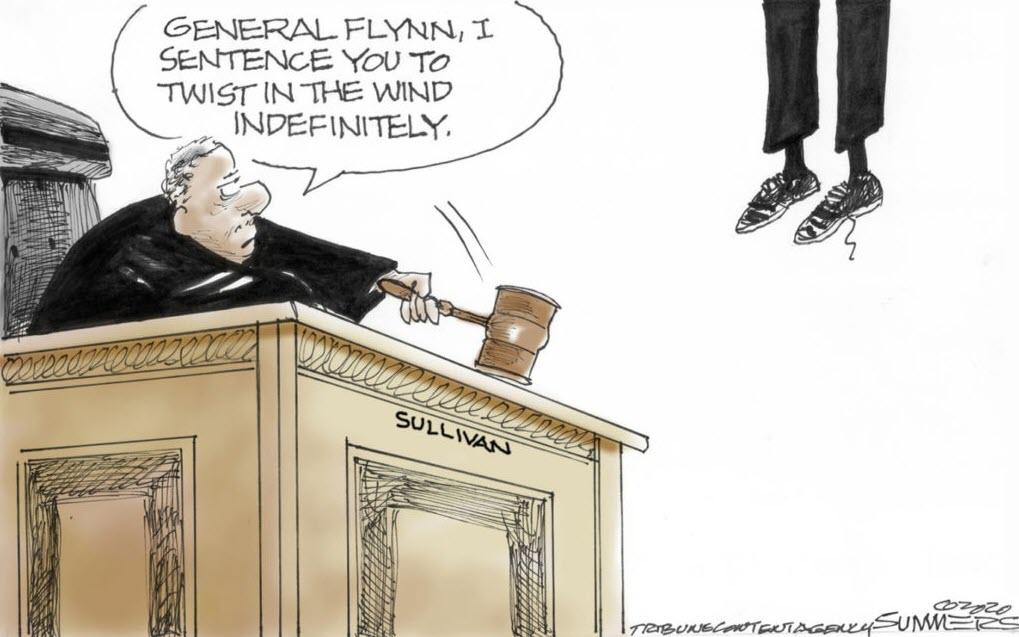

Faced with no dispute between the parties, Sullivan decided to create a contested case by inviting in third parties to create a conflict and now is suggesting that he may substitute his own criminal charge rather than let Flynn walk free. In the past, I have publicly praised Sullivan. However, this is fast becoming a case of gross judicial overreach as the court appears to assume both judicial and executive powers. Sullivan can disagree with the exercise of prosecutorial discretion, but he cannot substitute his own judgment for it.

“At the appropriate time, the court will enter a scheduling order governing the submission of any amicus curiae briefs,” Sullivan wrote. Never has a more innocuous line left a more ominous meaning. After that order, the judge proceeded to appoint retired Judge John Gleeson to argue against dismissal in the absence of a dispute between the parties. He is effectively outsourcing the argument to introduce a dispute. This move is nothing to celebrate.

A punishment by plebiscite

Amicus briefs are allowed by courts when outside parties want to be heard on some contested issue facing a court. Such filings are common in civil cases. This, however, is a criminal case. There are serious questions about the propriety of such third parties being asked to brief uncontested motions in a criminal case. The lives and liberty of individuals generally are protected from public demands for punishment. We do not do punishment by plebiscite in this country.

While courts have discretion to grant amicus or third-party arguments in civil cases, there is no counterpart under the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure. In fact, Judge Sullivan rejected such a request on Dec. 20, 2017, stating that “the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure do not provide for intervention by third parties in criminal cases. … Options exist for a private citizen to express his views about matters of public interest, but the court’s docket is not an available option.”

Sullivan’s earlier order was the correct one. It is dangerous to open up criminal cases for citizens to argue for convictions or enhanced punishments, particularly when prosecutors seek dismissal in light of prosecutorial error or abuse.

Indeed, former President Bill Clinton’s attorney general, Janet Reno, warned Congress against courts intruding on Justice Department decisions, stressing that “our Founders believed that the enormity of the prosecutorial power — and all the decisions about who, what, and whether to prosecute — should be vested in one who is responsible to the people.”

That is particularly the case where the motion benefits a criminal defendant. Indeed, it is difficult to imagine any basis that Sullivan could deny this motion without facing a rapid reversal.

However, the Flynn case has proved to be the defining temptation for many in discarding constitutional protections and values in their crusade against President Donald Trump. Experts are asking a court to consider sending a man to prison after the Justice Department concluded it can no longer stand behind his prosecution. Under this same logic, any defendant could face public outrage over an unopposed motion to dismiss, and a court could invite third parties to make arguments against him. Rather than protecting an unpopular criminal defendant from those outside clamoring for his head, the court is inviting them inside to replace the prosecutors.

Judges are not prosecutors

If Sullivan’s invitation for third parties to argue in a criminal case is unnerving, his suggestion that he might substitute a perjury charge is positively terrifying. Sullivan has compounded this judicial overreach by asking Gleeson to explore the issue, despite his public criticism of the administration’s handling of the Flynn case.

Under Sullivan’s theory, any time a defendant seeks such a dismissal (even with the support of the prosecutors) he could face a judicially mandated perjury charge. Faced with evidence of prosecutorial wrongdoing (which often arises after a trial), defense counsel (like myself) would have to warn clients that the court might just swap one crime for another.

The chilling implications of such a theory are being brushed aside by those eager to see Sullivan mete out his own form of justice. However, such an unsustainable decision would quickly careen out of control.

Consider the scenario. Sullivan knows that such a charge would not be prosecuted by the Justice Department. However, Criminal Procedure Rule 42 states that such cases are to be prosecuted by the government, but “if the government declines the request, the court must appoint another attorney to prosecute the contempt.”

So what is Sullivan going to do? He cannot force the Justice Department to prosecute a case that it considers to be unethical. He would have to enlist his own outside prosecutor after creating his own dispute with outside parties. If Flynn is convicted, Sullivan will have to order the Bureau of Prisons to incarcerate someone who was convicted by judicial design.Ironically, Sullivan is largely responsible for the current posture of the case. Flynn was supposed to be sentenced in December 2018 before the hearing took a bizarre turn. Using the flag in the courtroom as a prop, Sullivan incorrectly accused Flynn of being “an unregistered agent of a foreign country while serving as the national security adviser to the president of the United States. Arguably, that undermines everything this flag over here stands for. Arguably, you sold your country out.” He then questioned whether Flynn should have been charged with treason.

Flynn faced a relatively minor single count of false statements with the likelihood of no jail time — but Sullivan was suggesting that he could have been charged with treason, subject to the death penalty.

Sullivan then gave Flynn a menacing choice: “I cannot assure you that if you proceed today, you will not receive a sentence of incarceration. … I’m not hiding my disgust, my disdain.”

Flynn, unsurprisingly, opted to wait. Had Sullivan simply sentenced him, Flynn would have been formally convicted and sentenced — making any later motion more difficult while the case was on appeal.

Fortunately, while H. L. Mencken once described a judge as “a law student who marks his own examination papers,” our system allows for appellate review, and few judges would give such decisions a passing grade. The fact is, such a judicially constructed case would be effectively dead before it could be properly captioned for docketing. The problem is that Flynn would be left twisting in the wind as others use his case to make extraneous points.

Michael Flynn has the curse of being useful. He was useful to investigate for officials like FBI special agent Peter Strzok, former FBI Deputy Director Andrew McCabe and former FBI Director James Comey, though investigators found no underlying criminal conduct. He was useful to special counsel Robert Mueller, even though the same investigators apparently did not believe he intentionally lied to them. He now is useful to a court that seems intent on staging a criminal case of its own making.

Of course, at some point, when Flynn stops being so useful, justice might be served with the dismissal of this abusive case.