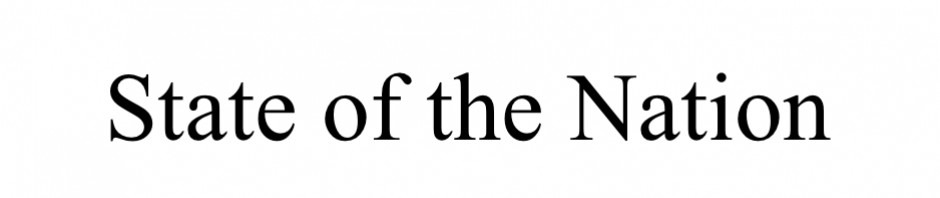

An exhibit about the wealthy Jewish Sassoon family is on view at The Jewish Museum in New York City through Aug. 13, 2023. Photo-illustration by Attributed to William Melville. Portrait of David Sassoon. Oil on canvas; 41 ½ × 33 in. (105.4 × 83.8 cm). Private Collection/The Jewish Museum; Installation view of the Sassoons at the Jewish Museum, Kris Graves

An exhibit about the wealthy Jewish Sassoon family is on view at The Jewish Museum in New York City through Aug. 13, 2023. Photo-illustration by Attributed to William Melville. Portrait of David Sassoon. Oil on canvas; 41 ½ × 33 in. (105.4 × 83.8 cm). Private Collection/The Jewish Museum; Installation view of the Sassoons at the Jewish Museum, Kris Graves

About six miles south of The Jewish Museum in New York, where an exhibit on the Jewish British merchant family, the Sassoons, is on view until Aug. 13, lies Chinatown’s Chatham Square. In the center of the square is a bronze statue of Qing Dynasty official Lin Zexu. The words “Pioneer in the War Against Drugs” are carved into the red granite pedestal upon which he proudly stands, in recognition of his efforts to rid China of opium in the mid-1800s.

By the time Lin became a government official in the 1830s, an estimated 10% of the Chinese population was addicted to opium (compare that to 3.8% of the U.S. population that abuse opioids today, which we consider an epidemic).

The Sassoon family dominated the opium trade in China, and the exhibit honoring them displays numerous treasures and artifacts they were able to collect, thanks to their opium-fueled wealth. In an age where the Sackler family’s name is being removed from museum buildings because of its ties to the U.S. opioid epidemic, it is no longer appropriate to celebrate artifacts like the ones the Sassoons were able to collect because they profited from China’s addiction without the full context.

The Jewish Museum does not hide the fact that much of the Sassoon family’s wealth derived from opium, but it does not reckon with its consequences either.

The exhibit has a full-wall text that details the fact that opium was illegal in China. The importation of opium was illegal under Chinese law — with edicts issued in 1796, 1813, 1814 and 1839 — but British merchants defied the law and smuggled it in.

“For more than 60 years the sale of this drug was to form the principal source of revenue for the British Indian Empire in its relations with China,” wrote historian Jacques Gernet in A History of Chinese Civilization.

This brief history is inadequate in capturing the full harm of what opium did to China. In addition to ruining individuals and families, opium led to inordinate amounts of corruption as well as a massive trade imbalance, exacerbating China’s already weakened economy. The Opium Wars and the resultant unequal treaties brought China to its knees.

In 1839, the Qing emperor sent Lin Zexu to the city of Canton (today, Guangzhou) to enforce the law. Lin immediately seized and destroyed 20,000 cases of British opium and ordered the responsible British merchants to leave Canton. The British government retaliated, sending in troops to attack various ports in what would become known as the First Opium War.

As soon as the British sent in their formidable navy, the Chinese had no other option than to surrender and sign the Treaty of Nanking in 1842. Under the treaty, the Chinese government had to pay 21 million silver dollars to the British, open various ports to opium trade, and allow for British “concessions” with extra-territoriality, meaning British law, not Chinese law, would govern the people of those areas. Before and after the treaty, British merchants like the Sassoons profited from the Chinese people’s opium addiction.

While The Jewish Museum effectively humanizes the Sassoons, the victims of their wealth — the Chinese — are not given the same courtesy. The museum could have featured passages from diaries written by Chinese people fighting against the opium trade, or video interviews with Chinese historians discussing opium’s impact. Lin Zexu himself kept a diary, and his 1839 letter to Queen Victoria, pointing out the immorality of the opium trade and asking her to stop it, is easily accessible on Wikipedia.

Even noting the price of some of the Sassoons’ artifacts in terms of cases of opium and how many people’s addictions that would have fed could have been a reminder throughout the exhibition — not just on one wall — of the Sassoons’ true impact on China.

Increasingly, museums are choosing not to separate artists from their art, or collectors from their artifacts. Take for example, the current debate surrounding Pablo Picasso. The fact that Picasso was an abusive misogynist has long been ignored by curators; instead the focus has been solely on his “genius.” While Picasso’s artistic brilliance should be highlighted, artist and art critic Shannon Lee wrote in The Picasso Problem: Why We Shouldn’t Separate the Art From the Artist’s Misogyny that “an artist’s flaws ought to provide us with potential opportunities to revisit and re-contextualize their work.” With each exhibit of an artist with a flawed or controversial history, curators and museum goers should be asking themselves who, if anyone, are this particular artist’s victims, and whether or not they have a voice in the exhibit.

The Brooklyn Museum, in its current exhibit It’s Pablo-matic: Picasso According to Hannah Gadsby, is daring to do just that. Co-curated by comedian Hannah Gadsby, who became famous because of her riff on Picasso’s treatment of women, the show not only contextualizes Picasso’s achievements, it also showcases feminist artists who, in their works, play upon Picasso’s legacy.

For the Chinese people today and their diaspora, what happened in the 19th century is not an artifact of the past that should be glossed over as it was in The Sassoons. The Jewish Museum has a proud legacy of pushing the art world forward but, by failing to fully revisit and re-contextualize opium’s toll, it missed an opportunity to serve as a vanguard on how precisely museums should address the horrors of a collectors’ wealth.

___

https://forward.com/opinion/553962/the-jewish-museum-sassoon-sacklers-opium-addiction/