The Lawsuits That Could Decide the 2020 Election

The pandemic means elections will look different, prompting more than 228 lawsuits. Here’s what law professor Justin Levitt thinks you should know about them.

By ZACK STANTON

POLITICO

[Editor’s note: This guy is very smart but has missed the boat at least twice: the 2016 election was massively rigged for Hillary, as the request by Jill Stein for recounts in Wisconsin, Pennsylvania and Michigan, in particular, revealed; and voter fraud using mail-in ballots occurs frequently. Check out the second Need to Know (4 August 2020) and the premier (3 August 2020), for an overview of how things stand with the greatest scam in world history.]

It’s not hard to imagine that in two months’ time, broad swaths of the country will be mired in Florida 2000-style chaos.

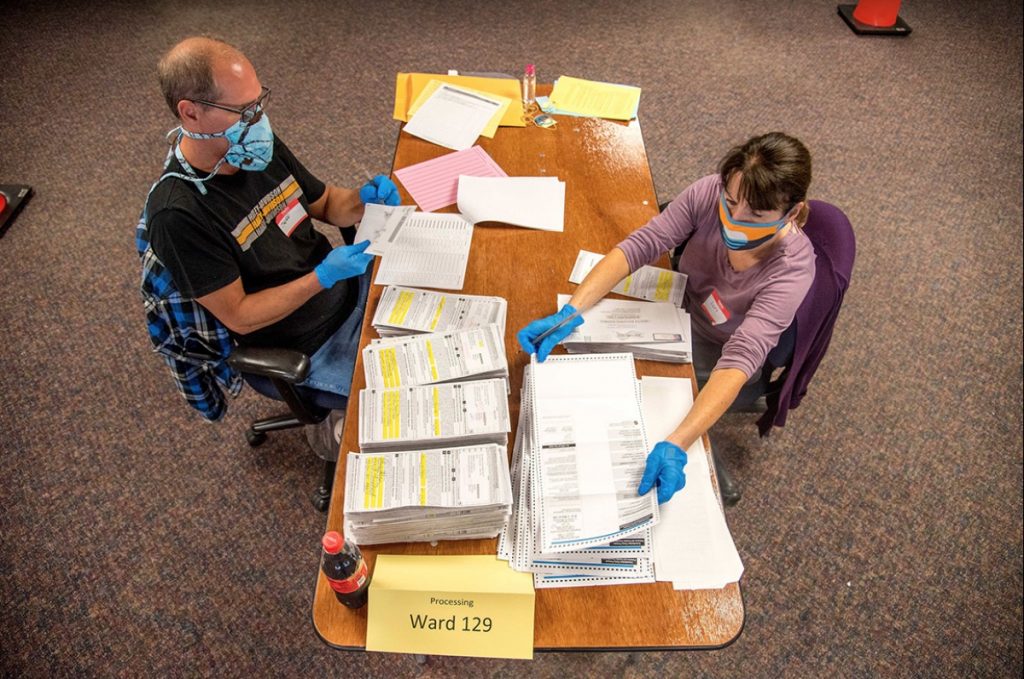

The pandemic is transforming the ways Americans will cast their ballots. Under-resourced election officials are straining to update voting processes in time, with fewer in-person polling locations and greater reliance on mail-in balloting. The president has repeatedly spread false claims that absentee voting is rife with fraud. Slow counts of those absentee ballots could very plausibly lead to replays of the infamous “Brooks Brothers riot”—when hordes of gray-suited DC-based Republican staffers descended on the Sunshine State—at election offices throughout the country.

“The pandemic is a once-in-a-century change in circumstances,” says Justin Levitt, a law professor at Loyola Marymount who specializes in election law. “And in many ways, continuing the status quo as if the world hasn’t changed is its own way to restrict voting.”

But those changes in long-familiar voting procedures have led to a bumper crop of lawsuits that could blow up into mini Bush v. Gore-style cases that further rupture the divide. Already, the pandemic-inspired election changes have prompted the filing of at least 228 lawsuits, according to Levitt, who tracks the litigation on his website.

And where the 2000 election was decided with a 5-4 Supreme Court ruling that ended the Florida recount and prompted Al Gore to concede and accept the legitimacy of the ruling even as he disagreed with it, it’s hard to imagine President Donald Trump voicing similar faith in the process if he loses in November.

“Remember, this is a president who claimed that there was a massive fraud in an election he won,” says Levitt. “We have had peaceful transitions of power because We, the People, have believed that it is possible that more people who disagree with us actually cast ballots—that the possibility exists that we might be in a minority. And if that is not even a conceptual possibility, that’s a real danger to democracy and to the election process. If you cannot conceive that you might be in the minority, there’s no possibility of achieving change through voting nor of achieving legitimacy through voting.”

Levitt, for his part, doesn’t think a Brooks Brothers riot is any more likely in 2020 than it was in 2000, but says there’s good reason for concern.

“The more the president attempts to suggest without evidence that the election is being stolen, the more that people feel like they’ve been aggrieved and need to take the process outside of the normal dispute-resolution mechanisms,” Levitt says.

He wants to remind people that the courts are one of those mechanisms. “There are always miniature Bush v. Gore cases, they just don’t always decide the presidency,” says Levitt. “They happen in every election cycle, usually in a race way down the ballot. It’s just you never hear about them.”

What do those 200+ lawsuits look like? Are we hyperventilating about this needlessly? And what pieces of litigation concern actual experts on voting rights? With early voting just days away from starting and Election Day two months away, POLITICO spoke to Levitt to sort through it all. A transcript of that conversation is below, condensed and edited for length and clarity.

Stanton: In terms of election lawsuits already in the works, what are we seeing?

Levitt: We’re seeing a lot. And we’re seeing it much earlier this year than past cycles—and that might well be a good thing. In part, that’s because when the pandemic arrived, it arrived during the primaries. And it arrived in a way where some executive and legislative officials were willing to make changes, some weren’t, and some couldn’t because the relevant rules are embedded in state constitutions and aren’t susceptible to change. And so, unsurprisingly, when we have circumstances that have really changed and rules that can’t change or don’t, people run to the courts—one other agent we have to modify rules for particular circumstances. And this once-in-a-century pandemic is a very particular circumstance.

We also got evidence in real time about how the pandemic would affect voting in the primaries. This was far less speculative than some cases are. In many ways, we knew which problems were encountered, and that gave the courts firmer footing to rule earlier in the cycle than we might otherwise see—we were getting decisions in June, July and August, when there’s still time to implement them, rather than waiting until October and running into chaos.

“Unsurprisingly, when we have circumstances that have really changed and rules that can’t change or don’t, people run to the courts.”

Stanton: You track the number of election-related lawsuits that have been filed. I understand that we’re now well above 150 cases?

Levitt: It was 226 the last time I checked. It’s moving very quickly.

Stanton: In terms of the number of voters potentially affected by these lawsuits, what are we talking about?

Levitt: Actually, I have to apologize: It’s 228 cases, and I haven’t added a couple, so it’s probably 230. It’s difficult to track. How many voters does this affect? I don’t honestly know. The better way to measure is this: There’s litigation now in 43 states, D.C. and Puerto Rico. And in a way, the litigation affects all of the voters in each of those states, not because it’s contesting the conditions that every voter will use to cast their ballots, but because it alters the framework under which the elections are held. Even a case that’s about just one candidate getting on the ballot affects the choices of who people will be able to vote for.

By the way, I’m tracking the pandemic-related election cases. But there are other cases, including a big one in Florida, that aren’t about the pandemic. So that is not to suggest that the states that aren’t on this particular list are free of election litigation; they just happen to be free of litigation based around the pandemic.

The second category has to do with mail-in ballots. Some of these lawsuits would’ve been brought in nonpandemic times. There is a string of litigation about how people get notified of mistakes in the absentee process—mismatches in signatures that voters sign to their absentee envelopes, which are then matched against their signatures in elections officials’ records—and whether they have a chance to fix those mistakes. Litigation about the absentee process picked up speed considerably when it became clear that far more of the public is going to vote by mail this year than normal. In 2016, I think about a quarter of ballots nationwide were cast by mail. So you see litigation over deadlines for mail-in ballots, or provisions about assisting people with ballots, or opportunities for voters to correct mistakes, or the excuse you may need to provide to vote absentee, or postage on absentee ballots, or the witnesses and notaries required by some states.

“The fight this election cycle has never been about moving literally everybody to vote by mail.”

The third category has to do with in-person voting. Even in states that are “universal” vote-by-mail, you almost always have an option to go down to the county office and drop off a ballot in person or fill out a ballot in person. It’s not truly universal vote-by-mail; it just means everybody has the option. The fight this election cycle has never been about moving literally everybody to vote by mail; it’s about increasing the opportunities to vote by mail to mitigate serious capacity constraints for those who have to vote in person. Just like there are people who are hard to count in the Census, there are people who are hard to mail, and populations that really depend on in-person voting—very rural and very urban, minority communities, those who face issues like language access, people with disabilities. So there’s litigation over the hours of early voting, over curbside voting opportunities, over the availability of dropboxes and other in-person places to return the ballot. And those lawsuits are almost entirely pandemic-related.

And then the fourth category is pushback back against all the other three: that the administration of the election shouldn’t change. The other three categories have to do with people asking the courts to change or modify the rules for this election because of the pandemic and because of changed circumstances. Sometimes, elected officials or legislatures have changed the rules, and this litigation is pushing back against those changes, mostly under the notion that the officials or legislatures have overstepped and may not have the authority to make the changes they’ve made.

Stanton: What are the most potentially consequential election lawsuits in the works?

Levitt: It really depends on how long your view is. There are cases where ballot initiatives to reform redistricting in states have been tossed off the ballot because they came in short of the number of required signatures because of the pandemic. If they had made it on the ballot, would those have changed the redistricting process, which changes the political landscape in a state for the next 10 years? Maybe. So, from one point of view, it’s enormously consequential long-term. From another point of view, it doesn’t affect the conditions of voting in the November election itself. It depends on your time horizon.

In terms of the way people vote, I think some of the more consequential cases are likely to be involve the opportunity to correct mistakes—sometimes mistakes by election officials, sometimes mistakes by the voters. And this is something I flagged because of a series of cases that aren’t specific to the pandemic, but definitely picked up speed and volume. They have to do with getting notice of a problem and getting the opportunity to fix it—core, basic fundamental legal concepts. “Procedural due process” is the legal name for it. Nonlawyers will recognize it as basic fairness: If you’re going to throw out my ballot, tell me why and give me a chance to fix the problem before you do.

There are more opportunities for unintentional error both by voters and by election officials in the mail-ballot process than with in-person voting. And as a consequence, the increase in voting by mail across the board increases the importance of these “notice and cure” procedures and the lawsuits to make sure that procedures are in place. More people will be voting using a system that’s less familiar to them personally, and election officials will have to work harder and faster to process many more things in a short amount of time. Both of those things are a recipe for predictable mistakes, which aren’t a problem as long as there’s a way to fix them. Those lawsuits may seem like a small thing over small procedural steps, but they may be among the most important in terms of the number of ballots cast and processed.

With respect to voting in the general election, there’s another “it depends”: It depends whether the case is consequential based on what it is arguing in theory, or whether it’s likely to work in practice. There are some cases asking for a fairly mammoth reconfiguration of local election practices, both to restrict access and to improve access—different cases in different places. Each is unlikely to succeed. Courts don’t like micromanaging all the aspects of an election. There are discrete elements that courts will address, but they don’t like putting themselves in charge of an election administration. And getting this close to an election, we’re just running out of time to make very big changes to the process. Those cases would be enormously consequential if they yielded an outcome, but it’s extremely unlikely they’re going to.

There are also cases that are brought by the political parties, either the Democratic National Committee, Republican National Committee and their affiliated parties, as well as the campaigns themselves. I don’t believe the Biden campaign has brought a case yet.

Stanton: But the Trump campaign has.

Levitt: They have. Three come to mind right off the bat. And those cases may be consequential not only in what they’re asking for, but in telling you where the major political parties seem to have priorities.

Stanton: One of the cases the Trump campaign filed is about restricting the number and location of drop-off boxes for absentee ballots in Pennsylvania, right?

Levitt: It’s about a bunch of stuff in Pennsylvania, drop-off boxes included—about whether there can be dropboxes, about whether individuals can poll watch at dropboxes, and a number of other procedures Pennsylvania put in place that the Trump campaign doesn’t like.

I should say that there are three suits that I’m aware of where the Trump campaign has brought the case in its own name. But they or the RNC have intervened in cases others have brought, as defense. When you see a party put its own name on a case, or when you see a campaign put its name a case, that is also a political statement about what they want you to know specifically they are fighting about. So it’s of messaging importance in addition to the legal importance attached to it.

Stanton: In the Pennsylvania case about ballot drop-off boxes, what is the basis for their case?

Levitt: The political basis or the legal basis?

Stanton: You can go either way.

Levitt: In terms of the political basis, the Trump campaign has claimed not only that there’s a particularized legal problem, but also that the implemented election measures open the opportunity for widespread fraud. This is very much in keeping with the president’s own messaging—founded or unfounded, warranted or unwarranted—about opportunities for widespread fraud.

In these instances, in addition to the narrow legal claim that the campaign is making—some of which has merit, some which are not crazy thoughts—there’s the messaging reinforcement: The Trump campaign wants you to know that these measures may increase the potential for fraud. I say, “wants you to know that,” but I don’t actually believe that these measures significantly increase the potential for widespread fraud. If you ask election officials, across the board they will tell you that they know how to run secure elections, and that while there are always opportunities for individual glitches or mistakes or even wrongdoing, the system is pretty secure against widespread fraud. And from all available evidence, they’re right. Nevertheless, the Trump campaign wants to put out a different message.

Stanton: Looking at the lawsuits still in play, which ones give you the most concern?

Levitt: Ah, that’s such a good question. There are particular resolutions I’m angry about. There are particular battles that I think are important. There are cases where I fear that relief that has been granted correctly will be overturned or paused. And there are cases where people have asked for tremendous changes, and where I’d be worried if they got what they were asking for, but I don’t think they’re going to get what they’re asking for. Among the 228 lawsuits, it’s hard to pick a favorite or least favorite child. [Laughter]

Stanton: You have an expertise in voting rights. You worked on the issue at the Department of Justice. If you were trying to restrict voting through lawsuits, what would you be doing at this point in time?

“The pandemic is a once-in-a-century change in circumstances. And in many ways, continuing the status quo as if the world hasn’t changed is its own way to restrict voting.”

Levitt: Honestly, there aren’t many ways that the courts have accepted to clamp down on present procedures. The main claim for clamping down on present procedures, is “these procedures cause fraud”—lots of screaming, all caps. Whatever the efficacy of that position in the court of public opinion, the courts that are actually courts demand evidence. So I don’t know that there’s much utility in using the courts to restrict voting if we’re starting from the status quo.

But the pandemic is a once-in-a-century change in circumstances. And in many ways, continuing the status quo as if the world hasn’t changed is its own way to restrict voting.

The world has changed around us. Many officials in many places have acknowledged that. Some have not. Some can’t, because their state’s constitution embeds rules that aren’t pandemic-appropriate, and sometimes state actors have no legal ability to resolve those problems outside of the courts. But pretending that everything is the same in 2020 as in prior years actually amounts to an effort to restrict the vote, because everything is most definitely not the same in 2020 as it’s been in prior years. There are plenty of ways outside of the courts, unfortunately, to constrict the ability to vote. In the courts, the most efficacious way to constrict votes is not to ask for a change in current processes, it’s precisely to fight back against changes in a world that requires a different approach to voting than we’ve had in the past.

Stanton: Talk about that different approach. In light of the pandemic, what needs to change about voting?

Levitt: Three things—and a fourth is the predicate to changing any of it: money. Unlike the federal government, most local officials can’t spend money they don’t have. We’re getting to the point where if they don’t get the money they need, they may not be able to do what is necessary before the election.

What are the three things that really need to change? One, we need to recognize that in-person voting capacity will be limited—not unavailable, but limited. Locations won’t offer themselves as polling locations and poll workers won’t come to the polls to the same degree they have in the past. That means a shift to accommodate alternatives to in-person voting, which means voting by mail. That has to happen. People have to be encouraged to vote by mail, if they can, in order to relieve the pressure on in-person voting.

When you have zero poll workers, there’s nobody to open the door. You can’t vote in person. This is not just an urban problem in any way.

One really vivid example of this came in Wisconsin’s primary. A lot of attention was put on the fact that in Milwaukee, 185 polling places were originally planned, but only five opened on the actual day of the election. That’s appalling and the result of the pandemic—poll workers and locations canceled last minute. What was far less publicized is that there were 100 small rural towns the week before Election Day in Wisconsin that had zero poll workers. And when you have zero poll workers, there’s nobody to open the door. You can’t vote in person. This is not just an urban problem in any way. This is a problem that affects all of us, just like the pandemic affects all of us.

The second big change is reconfiguring the in-person experience so that it is safe and as efficient as possible to move a large number of people through a smaller number of spaces. And sometimes that means creativity in the polling locations. We recently saw the NBA deciding to make all of its arenas available as elections centers. That’s wonderful. That’s not the solution, but that is part of a solution. We need creativity like that in locating and staffing polling places with depleted resources so that polling places are equitably located.

And the third big change is communication about all of this. The ways in which people vote may be different than in the past. Communication and clarity about exactly what that means is incredibly important. There has to be more of it, more clearly in more channels and more media than before, from election officials, from campaigns, from nonprofits, letting people know how to deal with the two other changes.

Stanton: On that topic of officials communicating about the election, President Trump has said mail-in voting is rife with fraud and that is, in effect, a way that the election will be stolen from him. I was in high school during the 2000 election, but I remember watching the Florida recount and seeing Republicans’ so-called Brooks Brothers riot that disrupted the count and made it seem like elections officials had a thumb on the scale in favor of Al Gore. Given Trump’s statements and the fact November will see a slower ballot count than past elections, what is the potential for mini Brooks Brothers riots at election offices across the country?

“This is a president who claimed that there was a massive fraud in an election he won.”

Levitt: I think it’s as small as it was in 2000. Which is to say: It happened, but it was only a few dozen people, and it disrupted the count, but not tremendously. There is certainly concern about groups and individuals seeking to influence the electoral process outside of the normal rules. Do I think it’s likely? Not particularly. But there’s concern about it for good reason.

The more the president attempts to suggest without evidence that the election is being stolen, the more that people feel like they’ve been aggrieved and need to take the process outside of the normal dispute-resolution mechanisms. And there are a bunch of those mechanisms. There are administrative mechanisms. There are judicial ones. And then there is taking to the streets.

Remember, this is a president who claimed that there was a massive fraud in an election he won, without any proof whatsoever that the fraud actually existed. I have no doubt that he will be loudly screaming about massive fraud come November, whether he wins or loses. What people choose to do with that is a different matter.

There’s another aspect of communication we should all get used to: There will be a number of states where we don’t know the outcome of the election on election night. It may not be that the states are too close to call. It may be that they’re too early to call—where we just don’t know the answer, not where the answer is unknowable. The fact that we may not know the answer on election night doesn’t mean the system’s broken; it means the system is working. It means that we are actually giving the vote counters time to count the votes rather than jumping to conclusions about who won or lost.

We, the People, aren’t very patient. We have to learn to be a little bit more patient than we’re used to. It’s just not in our muscle memory anymore. It used to be, a couple decades ago, that you went to bed on election night and found out who won in the morning. And a couple decades before that, you went to bed on election night and found out next week. The expectation that we know who won on election night 30 seconds after the polls close is relatively new, and not particularly realistic—and particularly unrealistic in this election. Again, that doesn’t mean that the election teeters in the balance. It could well be that the vote is clear, and we just haven’t been able to count it up yet. It’s really important for all of us to give that process time to work.

“The vote-tallying process is public in the vast majority of states. It is not a secretive, hidden process. … This is not the Illuminati deciding which ballots to put into the box and which ballots take out.”

The vote-tallying process is public in the vast majority of states. It is not a secretive, hidden process. It is open to being watched. There’s a very big difference between people gathering to ensure the integrity of that count, which is fine, and people gathering to disrupt the integrity of that count, which was in part the Brooks Brothers riot. This is not the Illuminati deciding which ballots to put into the box and which ballots take out of the box. It’s a number of extremely patriotic, extremely civic-minded officials, usually working at close to volunteer wages, who are simply counting up the ballots in as best and neutral fashion as they know.

Stanton: Part of that transparency in the ballot count, of course, is the legal process. Do you think that there’s a likelihood that there are going to be sort of miniature Bush v. Gore-type cases happening throughout the country?

Levitt: There are always miniature Bush v. Gore cases, they just don’t always decide the presidency. Court cases are part of the dispute-resolution mechanism. And they happen in every election cycle, usually in a race way down the ballot. It’s just you never hear about them.

“There are always miniature ‘Bush v. Gore’ cases, they just don’t always decide the presidency. … You never hear about them.”

Bush v. Gore came down to 537 votes in one tipping-point state. That’s a very small margin. We all focused on hanging chads, but that election was overdetermined. The margin of error vastly exceeded the margin of victory, based on a bunch of different things. There were problems at the polls. There were problems with registration. There were problems with purges of the voter rolls. There were problems with the butterfly ballot. There were problems with military ballots. There were problems with absentee ballots. These are little tiny problems that, in the normal course, would have been litigated and fought over, but wouldn’t determine a presidency. And it all mattered on a global scale because the presidency was in doubt.

Stanton: Final question: Bush v. Gore, as you noted, ended with the Supreme Court’s 5-4 ruling and then Al Gore conceding and talking about the need to accept the results of the process, even if he disagreed with the way it turned out. That sort of concession requires you to have some real belief in the importance of the process—some reverence for the rule of law. If President Trump loses reelection, it’s difficult to imagine him doing a similarly magnanimous concession and saying that we should trust in the process.

Levitt: Yes, it is difficult.

Stanton: And you note that the courts are a way to resolve these disputes. But lawsuits also presuppose that the results of due process lend legitimacy to the outcome. And if you question the very basis of that legitimacy, I’m wondering if that makes it more likely that people—Trump supporters, if he loses; or Democrats, if it plays out the other way—I wonder if that actually makes it more likely that people feel like they had something stolen from them, if not for these pesky judges. And then what the effect of all of that is on public faith in institutions and the rule of law.

Levitt: That’s the question you’re ending on?! [Laughter] So, yeah, that sort of magnanimity not only depends on faith in the process and faith in institutions, but regard for anything other than yourself. And that is a quality that we have seen lacking, unfortunately, in the current holder of the presidency. There is no question that the president’s rhetoric has consequences, including consequences on what his followers and others believe. And there is no question, if you look at his record, that he has shown not only disregard, but disdain, for the rule of law. That’s unfortunate, because that contributes to the view that some people have about the stakes in this election, and that because of those stakes, if they don’t win, something might have been stolen from them.

“If you cannot conceive that you might be in the minority, there’s no possibility of achieving change through voting nor of achieving legitimacy through voting.”

I don’t think it’s unique to “stolen by judges.” The rhetoric the president has used implies that if he doesn’t win, it’s been stolen by “fill in the blank.” That is profoundly dangerous. And I don’t want to minimize the danger of that at all. We have had peaceful transitions of power because We, the People, have believed that it is possible that more people who disagree with us actually cast ballots—that the possibility exists that we might be in a minority. And if that is not even a conceptual possibility, that’s a real danger to democracy and to the election process. If you cannot conceive that you might be in the minority, there’s no possibility of achieving change through voting nor of achieving legitimacy through voting. So that is scary.

Donald Trump is not the only one on the ballot on Election Day. And in the past, we have had figures claim fraud or impropriety in the results receiving pushback where their claims are unwarranted, including from members of their own party. Again, Donald Trump is not the only one on the ballot. There are a lot of figures in public office who are used to both winning and losing, and who believe in the importance of the process.

No matter what the result of the election, if there is no reason to believe there was widespread fraud, it will be important for officials of both parties to say so and say so loudly, because the person with the biggest megaphone in the United States has a history of making claims without basis and evidence that tend to destabilize the whole process. That will be as much a part of their legacy as whether they win or lose their individual races.